Most of us at some stage in our career have been subjected to a presentation or training course where some wit will solemnly pronounce that there is ‘no I in team’. This invariably comes from either your autocratic line manager (who really means there is no U in team), or some HR trainer who desperately would like to be in your team. This is meant to suggest that we should work together for the greater good, support each other, and generally have a happy slappy time. Teams that subsume the individual into the collective hive mind will perform better and be more productive. Or not. My experience of the best teams I (or should that be we) have worked with is different.

Most team-building exercises focus on consensus and conflict management, leading to convergence of behaviour, attitudes, dress sense, drinks preferences, and ultimately a Borg Collective. How this is achieved by dumping everyone in a field with planks of wood, rope and barrels without a Lord of the Flies moment continues to amaze me. My memories of these sessions are rarely pleasant, team-mates turning into team-hates with relief only when you finally get back home or to the office and (ig)normality. The only team-building exercises that I found of value were ones where the emphasis was on each person understanding how they came across to their colleagues, and what their colleagues truthfully thought of them. It took a bit of softening up to get people to talk openly but this fairly raw feedback was illuminating, and I know that almost everyone there understood for the first time how other people saw them.

Curiously, this approach was based on highlighting the differences and individuality of people, along with an understanding of each person by themselves and their colleagues. It is this acceptance of individualism, along with knowledge of their relative strengths and weaknesses that allows the team to organise itself into the most effective structure. Each team needs the right mix of roles covering thinkers, doers and communicators. A team assessment of where each individual’s strengths lie will allow the team to identify gaps, duplication and blockages, which if not addressed will result in conflict, weaknesses and ineffectiveness. From this insight, the action plan to improve the team is built on utilising the right people in the right roles, not trying to change people’s behaviour or attitudes.

IT leadership teams and departments tend to be filled with bright logical people who have progressed on individual merit, high on content and technical skills, but sometimes weaker on the business communication skills required (talking not grunting, eye contact, lack of odour).

Basing the team building on the actual challenges the team faces also helps to identify what is really required for the team to function. These real-world problems are rarely solved with lengths of rope (at least not legally), but with a specific focus on the outcomes required of the team. Also, as I’ve said before in Recruitment in the Time of Corona, psychometric testing that tells you that you’re a Plant (Triffid? Skunk Cabbage?) or an ENTP (tree taking a pee?) really doesn’t help either.

Making these teams successful is highly dependent on aligning their skills to the roles the team requires, and either training those with the right aptitude to take on the unfilled roles or bringing in people with the right skills. And having a manager who knows what they are doing would help, which I’ll cover in my next blog.

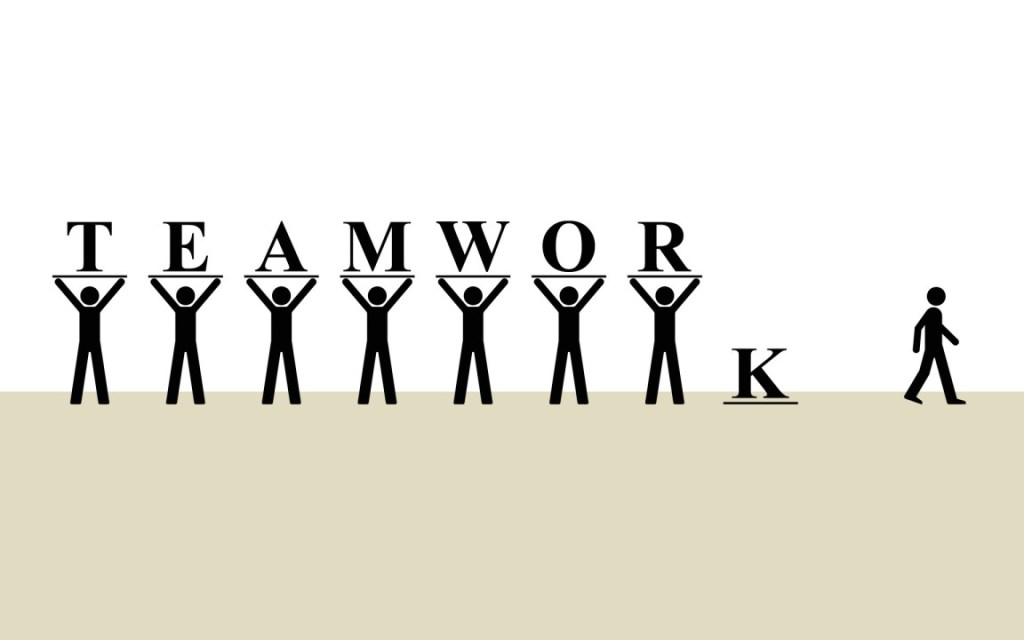

Remember though that there is a ME in team, albeit a bit backward, so keep up the teamw**k!

John ‘There’s almost a Moe in Team’ Moe

Leave a comment